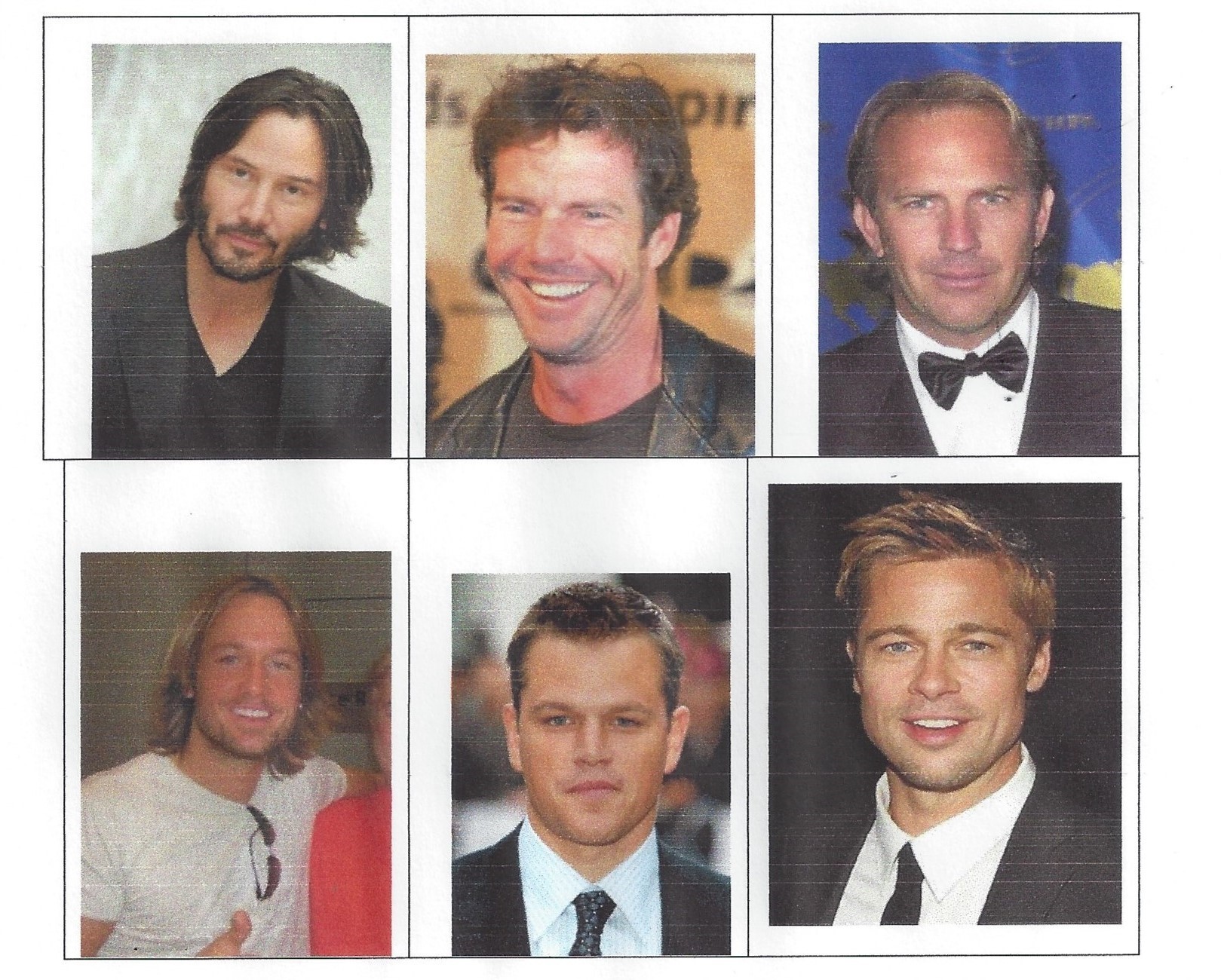

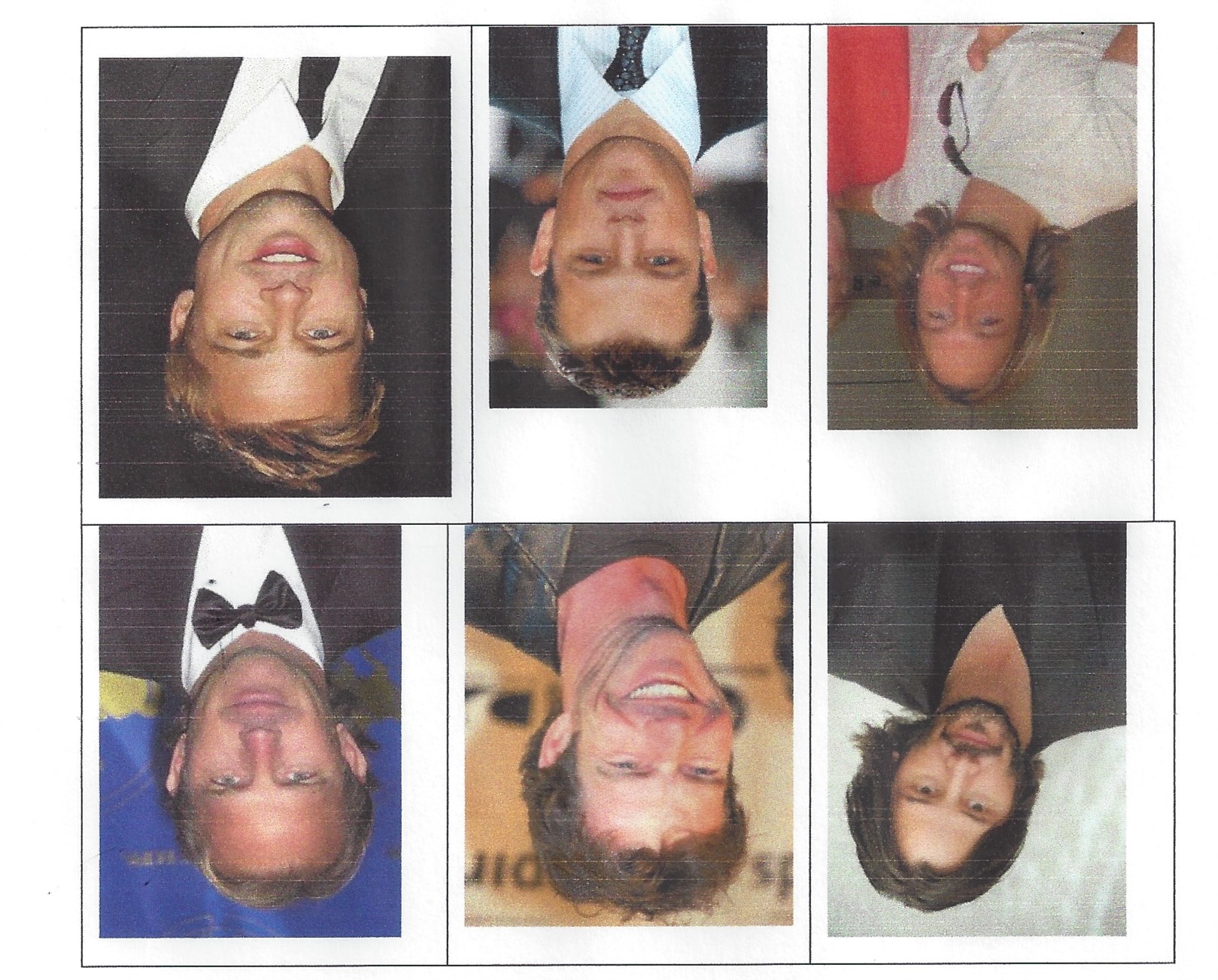

Can you recognize these men when viewed upside down?

We’ve seen the tricks to help you not get mixed up the letters b and d. I’ve used them myself. “Write bed.” I’d say. “b comes before d” so you can always write bed at the top of your paper to remind you of the sound for the letter (sound-symbol association).” Of course, you would be able to recite ”a, b, c, d, e, f, g,…”

I’ve had students make two fists and face their knuckles themselves, thumbs up like goal posts. The fist on the left looks like “b”, and on the right, the fist looks like “d”. Then there is a bat and a ball picture representing “b” and dog with a long upward tail picture representing “d”. And if you allow students to write upper case B and D in the middle of their sentences, this just presents a different problem. Is confusing b and b, p and q signs of dyslexia? Well, it may be, but let’s talk specifics about these tricky letters.

First, understand that dyslexia is a neurological issue and a deficit of phonological awareness. It is not a mental illness, which some insurances will say it is because it’s a Special Ed issue. (I say this because I diagnose for dyslexia and had one heck of a time finding the right insurance.) But if dyslexic students learn how to read, they most likely will exit Special Ed. Phonological awareness must be explicitly taught in a multisensory, systematic, sequential manner. That means face to face, not putting the child in front of a computer to read stories they’ve read before. It means direct (explicit) instruction must include visual, auditory, and kinesthetic activities.

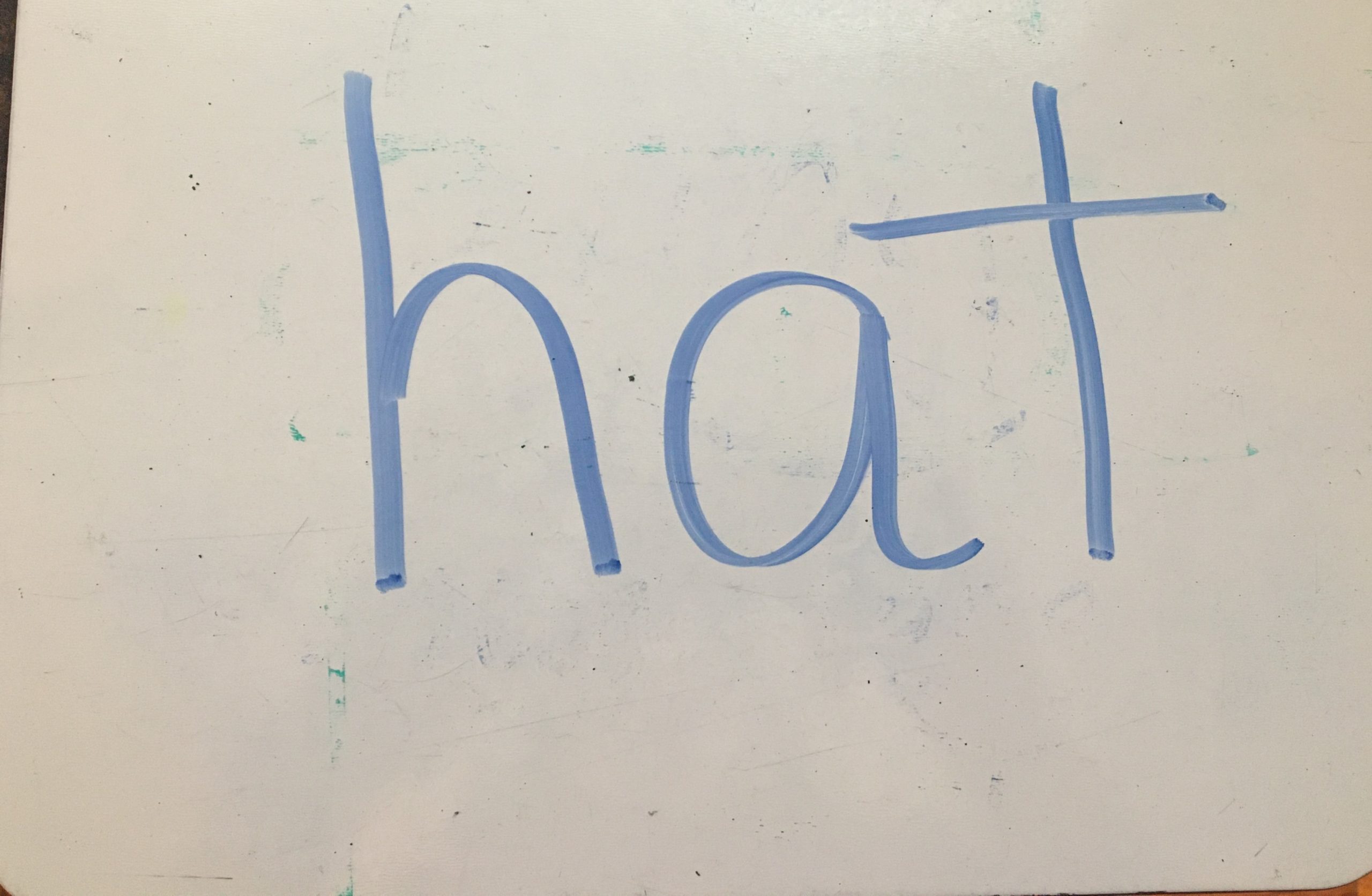

The letters b, p, d, and q are confused because the brain needs to learn to identify the letter name to the letter sound. If you hold a hat upright, then turn it 90 degrees, then turn it again 90 degrees, and then again, the same shape remains but it turned in different directions. But with b, p, d, and q, the brain doesn’t know necessarily if you are seeing the image upside down or not because the letter shapes could be just turned, and turned, and turned, and turned.

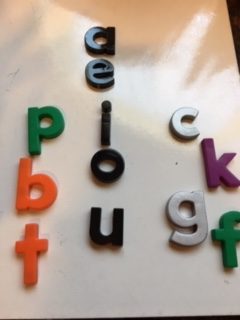

I was a teacher trainer for S.P.I.R.E. curriculum, and I learned that the creator of the program, Sheila Clark-Edmands, was a speech pathologist. She created S.P.I.R.E. to follow the order of a child’s speech development. That’s why she teaches a, i, o, u and then e. Separating the “i” from the “e” makes learning vowels much easier for kids. And what about consonants?

S.P.I.R.E. teaches the p and b sounds together in their Sound Sensible kit. (This kit teaches letter names and sounds for kinder and first graders.) The tricky thing with p and b is that one is voiced and one is unvoiced. If you put your hands over your ears or touch under your throat with two fingers, while you say /b/ you will feel a vibration. This is called “voiced.” If you do the same for /p/ you will not feel a vibration. “P” is unvoiced.

If you look in a mirror and see how your lips form the word “pam” and “bam” you won’t see any difference. The same is true for “vat” and “fat.” Now that you are the expert on voiced and unvoiced, which one is voiced and unvoiced for “vat” and “fat?” Again, your hands over your ears and say each word. Then put your two fingers under your throat (vocal cords) and do it again. ”V” is voiced, “f” is unvoiced.

When students are taught voiced and unvoiced sounds with their letters, the brain is being trained to recognize the letter-sound correspondence. Students accordingly learn how to write the letter “p” and practice it for a lesson and a reinforcing lesson. Three steps in the Sound Sensible program are phonological and the letter “p” is recognized as voiced and seen in pictures at the beginning and end of words. “B” and “d” are voiced and students see the letters at the beginning and end of words. Students need this explicit training in phonological awareness.

After “p” is fully understood, (mastery is 80%), students are introduced to “b”. Then they drill, drill, drill with “b.” They learn to write the letter “b” but continue writing the letter “p” because now they are adding the voiced “b” letter with the unvoiced “p” letter.

I hope you are recognizing that it’s not only a matter of “seeing” the letters in the proper order and remembering when to use them but understanding that a “p” sounds like /p/, with a puff of air when you put your lips together. The sound of “p” (written /p/) and the sound of “b” (written /b/) look the same with your lips together. Sound Sensible introduces “t”, before introducing “d”. And “q” isn’t introduced until Level 2 when it is introduced with “u” for “qu.” Are you understanding this? It is amazing! Kids who are confusing these letters most likely were never taught this way. Here are some more thoughts on teaching tricky sounds.

Another strategic move to helping students learn their letter names and sounds is not to introduce the vowels first. In Sound Sensible, all the letters (except q) are strategically taught. Then the only vowel taught is “a”. The short a sound (written /a/.) Students can learn a lot of three-letter words with one vowel. Reminds me of learning guitar. I learned three cords. I could play a lot of songs with three simple cords, G, C, and D. Anyway, I digress.

What helps children learn phonological awareness is a research-based multisensory reading program that is explicitly (directly) taught. I said this but it merits repeating, kids are not in front of a computer by themselves. The program is sequential, systematic, and structured (with intentional order followed lesson to lesson). It is cumulative, so as students learn new letters, they review previous letters. And lessons must be multisensory meaning students are using visual, auditory, and kinesthetic (moving, touching), oral (saying) senses. While students are being taught to their strengths, they are also addressing their weak areas. You can even listen to soft music in the background and have a candlelit (or wall fragrance) to allow all the senses to be engaged in the learning!

I want to ask you, how do you learn? Personally, I love listening to podcasts when I drive or walk. I take notes when I hear lectures or messages because whether I do or not, my brain thinks I’m going to be asked what I learned today! And, when I’m at home or in a classroom, I love using colors to highlight and organize. I personally like it quiet, but if something is in the background, I can still focus.

Our struggling readers can be taught to learn their letters. They need to work with a program five days a week and taught with fidelity. And they need to be taught by a trained teacher. Someone asked, “Can I work with my child?” Certainly, but most parents appreciate a break when it comes to teaching intervention.

Many things are involved with phonemic awareness. Students progress through stages of listening to similar sounds, categorizing sounds, rhyming, deleting sounds, and substituting sounds, and proper writing formation. They should also be playing fun games with these letter names and sounds. That will hold their interest! They feel smart!

Orton Gillingham is emotionally sound and builds confidence in the student. Teachers and students are familiar with the daily process (pedagogy) and look forward to lessons. Students are becoming strong learners and readers.

If you think I am an advocate for the Orton Gillingham curriculum, I am! If your school needs an excellent reading program, you need to look into SPIRE. California’s Assembly Bill AB1369 motivated Governor Newsom (also dyslexic) to earmark $100 million of our state’s education budget for early detection of dyslexia and intervention (kinder and first grade) for low-income students.

It behooves us to do early screening and not wait until third grade as we have done over the past twenty years that I’ve been an educator. Imagine saving a child’s self-esteem as well as the ability to keep him with his peers in the general ed classroom!

Finally, I want to close with this: The English language is tough! My kids are not dyslexic but they both struggled with phonics in first grade. They both received additional teacher support, either in first-grade summer school or three days a week after school, along with their peers. If classroom teachers taught the Orton Gillingham reading programs to all students, all would benefit from the multisensory teaching techniques.

So now here are the faces of the men in the above upside-down pictures. Can you recognize them more quickly now? Hope you enjoyed this week’s blog!